The project team evaluated the philanthropic sector in Geneva and Vaud on 22 indicators, divided across six categories. This chapter presents the most salient results that emerged from this analysis, which cover eight of the indicators and five of the categories (only the Collaboration category did not have any indicators included in the main section of the report). The results from the remaining indicators can be found in Appendix 2.

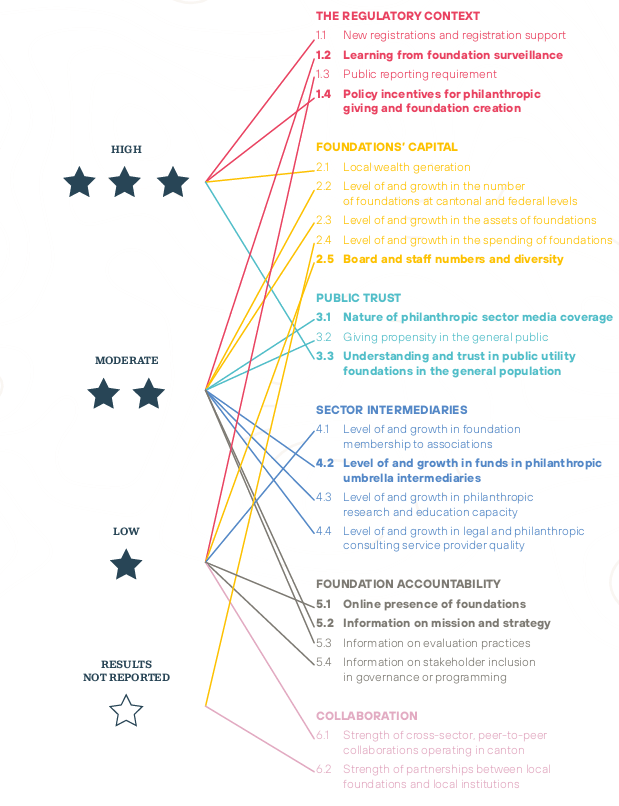

The purpose of the vitality assessment was to spur an evidence-driven collective effort to further position the Lemanic region as a global philanthropic hub. This first assessment, to be fine-tuned and repeated over time, can serve as the “shared measurement” of sector stakeholders, enabling each actor to contribute according to their own assets and capabilities. In line with the assessment, efforts should be weighed to improve the lowest-scoring indicators, without ignoring the others, whose scores should, at a minimum, be maintained. Figure 2 summarizes our measurements, with the results discussed in this chapter highlighted. The data collected for two of the indicators (2.4 and 6.2) did not permit us to draw conclusions solid enough to be included in the report; Appendix 2 contains further details.

Figure 2: Summary of indicator results

The Regulatory Context

1.2 Learning from foundation surveillance

In Switzerland, foundations are subject to oversight at one of three levels: communal, cantonal, or federal. The latter two cover essentially all foundations in both Geneva and Vaud. Foundations operating within their canton are generally subject to surveillance at the cantonal level, while those operating across cantons and/or internationally are surveilled at the federal level.

A core task of the cantonal and federal foundation surveillance authorities is to request annual reports from foundations and to screen these reports against risk criteria defined by each authority.18 While specific foundation-by-foundation information remains confidential, aggregated indications of risks across the sector can provide invaluable guidance to the sector on deficits that could be addressed through education or professional service providers. This study newly surfaced such indications from the cantonal surveillance authorities in Geneva and Vaud, and shows differences in the current surveillance practices and the definition of risk categories.

In Geneva, 248 foundations (46% of the total supervised at the cantonal level) were considered by cantonal surveillance authorities to be at risk to some degree in 2017, compared with 130 (13%) in Vaud 2018. Geneva differentiates low, medium, and high risks, and the vast majority of cases are considered low risk, which explains the overall higher number of risk cases. This difference in the risk classifications, combined with the varying definitions of the risk factors themselves, make it difficult to compare the results across cantons.

In Geneva, according to data provided by the Autorité cantonale de surveillance des fondations et des institutions de prévoyance, the most common issue is non-compliance of documents (39% of at-risk foundations), followed by concerns on high administrative costs (22%). In Vaud, the percentage of cases with financial concerns is similar to that seen in Geneva, but the top risk categories are cut differently: 58 foundations (45% of those at risk) were listed for lack of liquidity, and 27 (21%) for over-indebtedness. Figure 3 below lists the most common risk factors per canton.

Figure 3: Surveillance risk categories and number of foundations considered at risk in Geneva and Vaud (2017/18)

Note: Data from 2017 for Geneva and from 2018 for Vaud

Source: Data from cantonal authorities

42% of sector stakeholders responding to the perception survey strongly agreed or agreed that surveillance helps foundations better manage their risks. Our assessment is that this activity could be further studied and reported, in collaboration with the authorities, to help professionalize the local philanthropic sector. While the concern that fully disclosing a risk assessment methodology might undercut its diagnostic effectiveness is legitimate, further uniformity in, and guidance from, the surveillance authorities regarding risk categories and criteria to watch would enable foundations to be more proactive about diagnosing and solving issues within their own administrations.

1.4 Policy incentives for philanthropic giving and foundation creation

To evaluate this indicator, several local legal experts were consulted to define the parameters that most underpin a supportive legal and fiscal context, and to evaluate the status of these parameters in Geneva and Vaud. As the following table describes, the respective tax authorities oversee a generally supportive environment. They have implemented efficient processes for requests for fiscal exoneration, while the Vaud authority tends to be more restrictive than its counterpart in Geneva regarding the compensation of board members and the possibility of giving abroad.

69% of stakeholders responding to the perception survey strongly agreed or agreed that the tax system is supportive of the philanthropic sector, in general agreement with the opinion of tax experts.

Table 1: Review of policy incentives for philanthropic giving and foundation creation

| Topic | GENEVA ASSESSMENT | VAUD ASSESSMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Clear definition of public utility for exoneration | “Public utility” is a fiscal concept not defined by law but by the conditions set for exo neration, including: 1) a purpose of general interest; 2) exclusive and irrevocable contribution of the funds; 3) disinterest; and 4) actual non-profit activity. | |

| Purpose of general interest | “General interest” is more broadly defined and interpreted in Switzerland than in many other countries. The only difference between the two cantons deals with activities abroad: the VD authorities require them to be strictly described and delimited in the statutes. | |

| Board member remuneration | There is no legal base for prohibiting remuneration of board members. However, tax authorities interpret that the condition of “di sinterest” is applicable to board members, who cannot be remunerated. For GE, the principle is that remuneration is not permitted but excep tions are possible with restrictive conditions (attendance fees or compensation for tasks that exceed the usual scope of the role). | As a principle, VD’s tax authority does not allow board remuneration. VD practice is more restrictive than GE, as the VD authority requires more explanations and supporting documentation in order to allow the compen sation of board members. |

| Possibility of having activities abroad | There are no restrictions: foundations located in GE can have activities exclusively outside of Switzerland. | Some restrictions exist. Foundations located in VD must have an activity that targets beneficiaries located in Switzerland. In practice, however, the authority seems less restrictive as they have agreed to exonerate foundations with activities exclusively abroad. |

| Ease to obtain fiscal exoneration and tax authorities’ practices | The GE tax authority is pragmatic, open to discussions, and provides pre-opinions. They also provide tools to facilitate the exone ration process (such as specific guides and a fast track process for simple cases). | The VD tax authority has a specific ruling department with a dedicated team. They are open to discussions, provide pre-opinions, and have reliable processing periods. The VD surveillance authority’s guichet unique is very helpful, as foundations have a single interlocutor and do not have to send documents to tax authorities separately. |

| Possibility of having economic activities | Foundations can have commercial activities with important restrictions. These activities must be ancillary, not preponderant. Shareholder foundations are possible although with restric tions in terms of governance. Impact investing is allowed. | |

| Tax incentives for donors (domestic) | The tax incentives for donors could be improved, but the sole fact that some tax in centives exist has a positive impact. GE and VD taxpayers are allowed to deduct donations from their taxable income equal to up to 20% of their net income. In GE, there is no minimum required amount; in VD, the minimum is 100 CHF. | |

| Cross-border donations | There are no tax incentives for cross-border donations. Efforts need to be made by Switzerland by negotiating bilateral or multilateral conventions to encourage cross-border donations. The current situation is not satisfactory, although a paid solution exists, in the form of the Transnational Giving Europe network. | |

The following references were used to differentiate the practices of the two cantons, and are relevant reading for new philanthropists in the region who are considering setting up a foundation:

- Documentation related to Geneva:

- Guilleminot, Maud, and Catherine Neuenschwander. “Exonérations fiscales: Procédures & Conditions.” Geneva Cantonal Fiscal Administration. 26 October 2015. Accessed on 9 August 2019 at https://www.ge.ch/document/presentation-exonerations-fiscales-associations-fondations/telecharger.

- République et canton de Genève. “Demander une exonération fiscale.”12 September 2017. Accessed on 9 August 2019 at https://www.ge.ch/impot-associations-fondations/demander-exoneration-fiscale.

- République et canton de Genève. Demandes d’Exonérations Fiscales: Procédures et Conditions à Remplir. Geneva: Administration fiscale cantonale, 2016.

- Documentation related to Vaud:

- Centre Patronal. La Gouvernance des Fondations. Exonération fiscale des fondations : contraintes et opportunités. Yverdon-les-Bains: HEIG, 2013.

- État de Vaud. "Exonération Fiscale | État De Vaud.” 2019. Accessed on 9 August 2019 at https://www.vd.ch/themes/etat-droit-finances/impots/impots-pour-les-societes/exoneration-fiscale/.

Foundations’ Capital

2.5 Board and staff numbers and diversity

Foundations in Geneva and Vaud have a total of 15,416 positions for board members (6,867 and 8,549, respectively), representing some 6 board positions per foundation on average. There are also a total of 563 director positions, of which no foundation can have more than one, in the two cantons, meaning that at least 20% of foundations have at least one professional staff member. The proportion of women in both boards and director positions is very close to the overall national averages for foundations, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Share of women by position in foundation leadership hierarchies (as of July 2019)

Source: CEPS Basel

Survey respondents from foundations in Geneva and Vaud were invited to provide further details regarding board and staff gender diversity in their own foundations as follow-up questions on the stakeholder survey. According to them, 31% of the board members of respondents’ foundations are women, which is in line with the cantonal and national averages. Respondents reported that 69% of the professional staff in their foundations (at all levels, not just top management) are women, although this is obviously a small, and likely unrepresentative, sample.

Clearly, gender diversity is just the starting point for analyzing broader diversity and relevant experience, and the philanthropic sector should aim to be a leader in this regard. Doing so, however, will require much more data than was available for this study.

Figure 5: Foundation management diversity.

The share of women is lowest in the highest ranks of foundations, a phenomenon consistent across Geneva, Vaud, and Switzerland. The share of women among board members mirrors the share in the National Council (29%) and is better than in the private sector (19%).

*Note: This number comes from responses provided as part of the perception survey, where foundation leaders were asked to indicate the percentage of female staff members in their own foundations.

Source: CEPS analysis and perception survey

58% of stakeholders surveyed strongly disagreed that foundation boards are diverse, considering gender, age or other dimensions of diversity. Only 42% strongly agreed or agreed that boards have all the right skills and experience, while 20% disagreed or strongly disagreed. Regarding staff composition, 45% of stakeholders agreed or strongly agreed that foundation staff members are diverse.

Public Trust

3.1 Nature of philanthropic sector media coverage

The study reviewed over 355,000 articles published in Geneva and Vaud media outlets from May 2017 to May 2019,19 of which 371, or 0.1%, were found to contain the search terms “foundation + public utility” and/or “philanthropy.” Considering that Swiss foundation giving represents 0.3% of national GDP, coverage appears somewhat low in view of the sector’s relative share of “investment” in the country, with the caveat that search engines may not have identified all relevant publications.

22% of perception survey respondents strongly agreed or agreed that local media coverage adequately informs the public about the philanthropic sector, a lower figure than expected. Respondents from Vaud rated the media coverage much worse than did those from Geneva: 67% disagreed or strongly disagreed that the media paints an adequate picture of the sector, significantly higher than the overall average of 47% disagreement or strong disagreement.

269 of the 371 articles were selected for a deep-dive analysis, after removing duplicate or otherwise non-pertinent results. 52% and 30% of these 269 had a positive or a neutral tone, respectively, while 18% carried a negative message.

The high share of positive articles is good news for the sector, but given that trust is fundamentally in the eye of the beholder, and in light of the low rating given in the perception survey, we settled on a low-to-moderate rating for the indicator. Some researchers have noted the tendency of negative articles to far outweigh the positive resonance of positive ones.20 We do not see this as a problem, however; indeed, constructively critical press coverage can be healthy and can spur important action and reform, insofar as it brings to light dynamics or practices that should be changed.

What the media says about local philanthropy

The majority of negative articles emphasized conflicts of interests between donors and their giving objectives or targets. Other general themes among the negative articles included political corruption, suspicious sources of wealth, maintaining power and privilege for the wealthy, substitutions of the role of the state, and concerns of poor governance and management.

Four themes dominated the majority of positive articles, influenced in part by recent events in the Lemanic region:

- Celebrating the value of foundations and philanthropy around themes of family values and the social engagement of the “next generation,” the innovation power of philanthropy, and, more generally, the dynamism of philanthropy in Switzerland

- Announcing the creation of the new Centre for Philanthropy at UNIGE and the potential of Geneva as an international solidarity and philanthropic hub

- Praising specific stories of philanthropic engagement in the region around numerous needs, such as project funding at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), advocating for technology in service of humankind, female entrepreneurship, vulnerable youth, preventing violence in schools, supporting the building of public pools or sailing events, animal protection, social services, and even the preservation of watchmaking skills

- Illustrating the potential of sustainable or impact finance, particularly around the International Committee of the Red Cross’s (ICRC) humanitarian impact bond innovation

3.3 Understanding and trust in public utility foundations in the general population

The public trust survey of 310 individuals aged 15-79 in Geneva and Vaud, conducted by the LINK Institute in June 2019, yielded a refreshingly positive outcome in terms of public understanding and trust, as highlighted in Figure 6. The importance of this result influenced our overall strong assessment for the public trust category. First, the vast majority of respondents (72%) were able to describe in relevant terms what a “public utility foundation” does or represents: 51% described it as acting “for the good of the community/society” or for the “common good,” while another 21% said that it does not seek to turn a profit.

Figure 6: Trust in foundations to work for the public good, by age group

Note: The question asked (in French) was the following: “To what degree do you agree with the following statement: Foundations work for the public good in the Lemanic region.” Respondents were asked to respond on a standard five-point scale: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree. The percentages presented above represent the share of respondents in each age group who responded either “strongly agree” or “agree”.

As noted in Figure 6, 54% of all respondents strongly agreed or agreed that public utility foundations act in the general interest, with particularly strong endorsement from 60-to-79-year-olds (73%, albeit in a limited sample of only 56 respondents). Younger age groups agreed with the statement less often—50% for 15-to-29-year-olds and 46% for 30-to-44-year-olds—although, again, the sample sizes are small. For all age categories, the vast majority of those who did not agree with the statement were neutral in their reactions: only the 30-to-44-year-olds either disagreed or strongly disagreed over 10% of the time (14.5%). Even so, these dissenting voices can have an outsized influence, particularly since they are most concentrated in an age group that is likely to dominate the political scene for the coming two decades.

The most striking result emerged from the Edelman Trust Barometer question, which asked respondents about their relative levels of trust in different institutions. Public utility foundations registered as the most trusted of any of the sectors offered as possible choices. 64% of respondents “trust foundations to do the right thing,” versus 53% and 51% for government and NGOs, and 39% and 32% for business and media respectively (see Figure 7).

We must add a few words of caution, however. First of all, as mentioned previously, the sample sizes are small, particularly for the results by age group (further details on the respondent pool and the methodology can be found in Appendix 1). Additionally, a bias may have emerged as a result of the question having been asked as part of a survey explicitly focused on the philanthropic sector and foundations, if respondents felt pressure to tell the interviewer what they believed the interviewer wanted to hear. Finally, it is also important to consider that older generations trust the sector more than youth do, especially when thinking about how to move forward with the political and policy measures needed to increase philanthropic vitality.

Figure 7: Trust in institutions to “do the right thing,” by age group

Note: The question asked (in French) was the following: “Below is a list of institutions. For each one, please indicate how much you trust that institution to do what is right using a nine-point scale where one means that you ‘do not trust them at all’ and nine means that you ‘trust them a great deal.’” The question was scored on a 9-point scale, where 1 represented zero trust and 9 represented complete confidence. The percentages presented above represent the share of respondents in each age group who reported scores between 6 and 9 for the selected institution.

Sector Intermediaries

4.2 Level of and growth in funds in philanthropic umbrella intermediaries

An umbrella foundation (referred to as a fondation abritante in French) is a relatively recent legal structure in Switzerland that shares some characteristics with the donor-advised funds common in the English-speaking world. The umbrella foundation itself holds no capital and gives out no grants. Rather, it is a shared administrative structure used by sheltered funds (in French, fonds abrités) created under its auspices. The sheltered funds are not legal entities, and therefore can be created more quickly and simply than an independent foundation. Furthermore, the shared administrative structure significantly reduces the operating costs for a sheltered fund, making it feasible to create a sheltered fund with far less start-up capital than an independent foundation. While the umbrella foundation’s board retains final authority over the grant-making decisions of the sheltered funds, most umbrella foundation boards allow the creators of sheltered funds wide latitude in their grant recommendations, provided that their grant-making is aligned with the regulations of their sheltered fund.

The two principal umbrella foundations in the Lemanic region, Fondation Philanthropia and Swiss Philanthropy Foundation, have existed for 11 and 13 years, respectively. Several newer structures also seem to be emerging, but little information is available regarding their stages of development. These include Fondation Ceres, founded in 2014 and associated with the Pictet Group; the Geneva office of the Fondation de l’Orangerie, associated with the bank BNP Paribas; Philigence; and MyOwnFoundation. These umbrella foundations come in two distinct groups, those like Philanthropia and Ceres that are associated with private banks for the benefit of their clients; and those that are “public” and operate independently, such as Swiss Philanthropy Foundation and MyOwnFoundation.

Fondation Philanthropia and Swiss Philanthropy Foundation have seen steady recent growth in their numbers of sheltered funds, from 39 combined funds in 2014 to 68 in 2018, which works out to a 15% annual growth rate. Sheltered funds remain, however, far from the mainstream, as evidenced by the enormous disparity between the 68 sheltered funds and the over 2,500 foundations in the canton. As will be discussed in the recommendations section, we believe that umbrella foundations and sheltered funds could and should play a much larger role in the Lemanic philanthropic sector, especially given the small size of the average Swiss foundation.

Total disbursements from these sheltered funds vary substantially year-on-year, but have ranged from 15-25 million CHF per umbrella structure annually in the last five years. The volatility is due to the pass-through nature of many sheltered funds, as well as the fact that each sheltered fund decides on its own disbursement strategy and schedule, rather than adhering to an overarching strategy at the level of the umbrella foundation.

Foundation Accountability

5.1 Online presence of foundations

Foundations in the Lemanic region are noteworthy for their general lack of online presence, likely linked to the fact that roughly 75% of all foundations in the region have no staff on payroll. Of the more than 1,200 foundations in Geneva, according to a database provided by the cantonal government, 61% do not have a website. Unfortunately, a corresponding database does not yet exist for Vaud, but a sample of 300 registered foundations in the canton, selected from a list of all foundations supervised at the cantonal level, yielded a very similar result, with 54% found to be lacking a website.

Deeper analysis enabled by the Geneva dataset shows that grant-making foundations are relatively less likely than other foundations to maintain an online presence: 65% lack websites, compared 51% for operating foundations. This result is somewhat surprising and concerning, given that grant-making foundations arguably have a greater need to communicate funding criteria, regulations, calls for proposals, and documentation and reporting requirements, even if they may not need to be as visible as foundations whose primary goal is fundraising (such as WWF Switzerland Foundation).

We do acknowledge that there are, at least in theory, offline ways in which foundations can communicate their missions, activities, and finances with the general public. That said, the offline world’s search engines are much more difficult to use than Google, especially for a person with no prior knowledge of a foundation, and a foundation with no online presence is therefore much more difficult to find. This may be especially true in Switzerland given the large number of small foundations in the country: a foundation with no physical office and no website essentially does not exist for the average citizen, unless it conducts activities or events with significant public visibility.

43% of respondents to the perception survey strongly agreed or agreed that foundations are present and visible on the internet, a surprisingly positive rating. In comparison with responses to other questions, this is a quite positive result, but one which seems too optimistic in light of the new quantitative facts generated by this study. For this reason, the overall rating given to this indicator is “low-to-moderate” in line with the clear quantitative data.

5.2 Information on mission and strategy

Even when taking into account the large proportion of foundations in Geneva and Vaud that lack websites, it would not have been feasible to analyze the information provided on all foundation websites in the two cantons. We therefore chose to analyze a random sampling of foundation websites. From a random sample of 150 foundations with websites (75 from each canton), we found that most share basic or comprehensive information about their strategy (as of June 2019):

- 16% mention only a simple mission statement

- 51% communicate basic information about their mission, thematic focus areas, activities and target groups

- 29% are more explicit about their strategy and mention the outcomes they seek

- Only 3% present a comprehensive theory of change, sharing inputs, outcomes, and impact expected from core activities for specific target group(s)

42% of perception survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that foundations publish adequate information on their mission and strategy, echoing the findings of the quantitative research.