Measuring Philanthropic Vitality: a Three-Pronged Approach

As we began our research into possible indicators that could be used to measure the factors that contribute to the vitality of the philanthropic ecosystem, it quickly became clear that a multi-pronged approach would be necessary. Such an approach would allow us to develop a methodology that would be rigorous, yet practical, and would constitute “action research” that yields relevant recommendations.

To begin with, “philanthropic vitality” itself is not yet a mainstream concept. It was thus often necessary to find and use data collected for other purposes, not all of which ended up being exactly what was needed. In addition, the highly federal and devolved nature of government and oversight in Switzerland means that the two cantons covered by the present study do not always collect the same data or report it in the same way, further complicating the research task. The quantitative portion of the study therefore represented our best attempt to compile a representative and informative assessment.

One of the challenges inherent in quantitative data is that it generally captures achieved outcomes or lagging indicators, whereas we are interested both in the state of the world today and inferences about its state in the future, and thus need to consider forward-looking “leading” indicators as well. We thus decided early on in the process to supplement the quantitative data with qualitative findings from a survey of philanthropic sector stakeholders in the two cantons. Given that one of the key goals of the study was to engage philanthropic sector actors in addressing the challenges that they face on a daily basis, the inclusion of a large number of direct inputs from these very actors allowed the study, remain as relevant as possible, and capture emerging issues. The survey was distributed not only to the staff and boards of foundations, but also to a wide range of intermediaries and service providers, including consultants, lawyers, accountants, and others who deal with philanthropy on a regular basis.

The third component of the study was born out of the fact that the philanthropic sector is supposed to serve the public benefit, but is nevertheless often misunderstood and may sometimes even be distrusted by the general public. We therefore decided to commission a representative survey of 310 total residents of the cantons of Geneva and Vaud, in which respondents were asked a series of questions regarding their understanding of and trust in foundations. In addition to providing a valuable snapshot of public opinion at the present moment, the results can be used for comparison with future iterations of this study to evaluate how opinions change (or not) over time.

Table Overview of the Six Vitality Categories

The following table provides a succinct overview of the indicators. It contains indicator definitions; the summary of their relevance as derived from experts, articles and studies; the measurement methodology applied to assess each indicator; data sources; and, importantly, the associated question(s) included in the stakeholder and public perception surveys.

Table 2: Overview of six vitality categories

| Indicator | Relevance | Measurement | Data Sources | Survey Agree/disagree |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Regulatory Context | 1.1 New registrations and registration support | New registrations indicate a positive momentum for philanthropy; pre-opinions by surveillance authorities is an enabling service | Number of new registrations (and liquidations) in GE & VD at cantonal and federal levels (2014-2018); share benefiting from a pre-opinion service (2018) | CEPS Basel GE & VD cantonal surveillance authorities. Federal surveillance authority |

The pre-opinion services by the surveillance authorities enable donors to realize their philanthropic projects |

| 1.2. Learning from foundation surveillance | Criteria represent risk factors to foundation effectiveness; aggregated results provide insights into sector development needs | Share of foundations under surveillance flagged for any risk criterion; top 3-5 risks by share of foundations at risk | GE & VD cantonal surveillance authorities. Federal surveillance authority | The control activities of the surveillance authorities help foundations better manage their risks | |

| 1.3 Public reporting requirement | Public reporting promotes effective governance, learning, grant-making, use of resources, collaboration and visibility | Is public reporting of foundation specific assets, spending and activities mandated? (Yes/No) |

Analysis of legal regime; Swiss Foundation Code (voluntary) | The publication of foundation specific data on assets, spending and activities (today voluntary only) contributes to increasing the vitality and public benefit of foundations | |

| 1.4 Policy incentives for philanthropic giving and foundation creation | Philanthropy is motivated both by self-actualization and fiscal benefits; fiscal incentives influence the amount given to a larger extent than the giving propensity | Compilation of major legal and fiscal regime attributes that positively versus negatively influence philanthropy and review by legal experts | Desk research of federal & cantonal legal and fiscal regimes; expert interviews | In general terms, the GE & VD fiscal regimes promote philanthropy | |

| 2. Financial and Human Capital | 2.1 Local wealth generation | Private wealth generation underpins the growth of philanthropic giving (incl. through foundations); generational wealth transfer also leads to endowing (new) foundations | Wealth generation in GE & VD / Switzerland (5-year trend) Number of millionaires in comparison to other cantons |

National statistics; Statista | NA |

| 2.2-2.4 Level of and growth in the number, assets and spending of foundations (registered at cantonal and federal levels) | Common sector statistics in countries where reporting is mandatory; enables understanding of the magnitude, vitality, and impact of institutional philanthropy | 5-year growth (2014-2018) for foundations registered at cantonal and federal levels in GE & VD; Drill down on foundations with assets > 10 CHF mn |

GE & VD cantonal surveillance authorities, CEPS Basel | NA | |

| 2.5 Board and staff numbers and diversity | Board member and staff diversity enhances innovation, brings new perspectives, broadens networks, increases community responsiveness and impact | Analysis of board and staff diversity, starting with gender diversity available from registry information | CEPS Basel | Generally, foundation boards are diverse (gender, age, etc.) Board members in general have the relevant competences and experiences to support foundations’ specific missions Generally, foundation staff is diverse (gender, age, etc.) (Foundations were invited to report their own figures) |

|

| 3. Public Trust | 3.1 Nature of philanthropic sector media coverage | Media influences trust in the sector, and the commitment of existing donors to do more | Ratio of articles covering philanthropy and public utility foundations as a share of all articles; ratio of positive to negative articles; top reasons for negative coverage | SwissDox article search (Suisse Romande Media) 2017-2019 | The local media informs the public adequately about the philanthropic sector |

| 3.2 Giving propensity in the general public | Countries differ deeply in terms of giving culture, which influences the level of giving | Participation in giving and volunteering in the general public and average gift size in Suisse Romande (GE & VD for volunteering) versus the national average | Swiss Fundraising, Swiss Federal Statistics Office, Enquête suisse sur la population active (ESPA), module on volunteer work | Individual giving is perceived well and valued by the public Individual volunteering is perceived well and valued by the public |

|

| 3.3 Understanding and trust in public utility foundations in the general population | Understanding leads to trust; trust influences the growth, quality, and diversity of philanthropic action | SECTOR EXPERT SURVEY: In general, the general public has confidence in public utility foundations (agree/disagree) PUBLIC SURVEY: What is a public utility foundation (open question)? Do public utility foundations act in the general interest in the Lemanic region (agree/disagree)? Are you aware of a specific contribution made to the Lemanic region by a public utility foundation (open question)? To which extent do you trust each sector listed below (incl. public utility foundations) to do the right thing (Likert scale)? |

|||

| 4. Intermediaries | 4.1 Level of and growth in foundation membership to associations | Organized philanthropic networks increase the capacity (access to knowledge, and skills thereby enhancing professionalism) of the sector as well as its impact, decreasing fragmentation and enabling peer learning | Growth in membership (2012-2018); Membership as a share of total foundations in the region; growth in association staff (2012-2018) for Suisse Romande | SwissFoundations; proFonds; AGFA (Swiss Fundraising, ZEWO for operating foundations) |

N/A |

| 4.2 Level of and growth in funds in philanthropic umbrella intermediaries | Umbrella funds help relieve the relatively smaller philanthropists of the administrative and financial burden related to the professional management of institutional foundations | Growth of funds under management and disbursement (2014-2018); Number of funds as a share of total foundations in GE & VD | Fondation Philanthropia, Swiss Philanthropy Foundation (Ceres and other nascent structures) |

N/A | |

| 4.3 Level of and growth in philanthropic research and education capacity | Philanthropic education through academic institutions or other increases the growth, quality and diversity of the philanthropic sector | 3-year (2016-2018) growth of teaching capacity (number of classes, students, professors, post-docs); research capacity (number of publications, articles awaiting publication funding); events (number of events, foundation partners) | GCP-UNIGE, IMD (and collaborating practitioners) | N/A | |

| 4.4 Level of and growth in legal and philanthropic consulting service provider quality | Services enhance organizational effectiveness and regulatory responsiveness | Growth in staff capacity dedicated to local foundation clients (2014-2018) | Survey of professional service providers | Do you use professional intermediaries for the daily functioning of your foundations? (yes/no/NA) If yes, to what extent are you satisfied with their services (Likert scale)? If yes, please indicate the providers you most often use (top 3) |

|

| 5. Accountability | 5.1 Online presence of foundations | Foundation transparency is a global trend and promotes trust (Chapter 1). It is a key principle in the Swiss Foundation Code | Share of foundations registered in GE & VD with websites | DDE (Geneva) and AS-SO (Vaud) foundation database; desk research | Foundations are present and visible online |

| 5.2 Information on mission and strategy | Accountability is rooted in respect for the public and seeks to provide clarity about what institutions are trying to do and why they are trying to do it. | Share of foundations with websites that have a) only a mission statement; b) thematic focus and some indication of activities; c) clarity on outcomes pursued; or d) theories of change/logic models and projection of outcomes and impact | Analysis of foundation websites and reports (150 in GE & VD) | Foundations publish adequate information about the mission and strategy | |

| 5.3 Information on evaluation practices | A foundation’s capacity to achieve its mission is linked to its ability to evaluate and learn from its activities | Share of foundations with websites that have a) no record of self-assessment; b) assessment mentioning some process or result indicators; c) reporting on specific grants, stories of outcomes, and/or participation in an accreditation scheme; or d) assessment with insights on what did not work, and shifted strategy | Analysis of foundation websites and reports (150 in GE & VD) | Foundations publish an adequate analysis of their impact | |

| 5.4. Information on stakeholder inclusion in governance or programming | Trust and effectiveness in foundations is linked to agreement with key stakeholders about the specific value they create in society | Share of foundations with websites that have a) no mention of stakeholder inclusion; b) evidence of problem issue research; c) voice of beneficiaries included through quotes, feedback; or d) formal inclusion of beneficiaries in advisory boards or regular consultations | Analysis of foundation websites and reports (150 in GE & VD) | Foundation stakeholders generally influence key program/project decisions through beneficiary consultation or other feedback mechanisms (Foundations are invited to add their examples of stakeholder inclusion) |

|

| 6. Collaboration | 6.1 Strength of cross-sector and peer-to-peer collaborations operating in canton | Networks of foundations collaborating either for fundraising or grant-making can strengthen the contribution of the sector especially around larger scale and more complex problems | Identification of cross-sector/peer-to-peer collaborations operating in GE & VD and assessment of key conditions for collective impact (yes/no): clear common agenda/goals; mutually reinforcing activities vs a joint project; shared measurement; backbone capacity; clear communications | Desk research; stakeholder survey | Do you know of examples of partnerships between several foundations or foundations and local government (public-private partnerships) working for the general interest? (yes/no/NA) If yes, to what extent do you believe this partnership is effective? (Likert scale) |

| 6.2 Strength of partnerships between local foundations and local institutions | Funding of major local institutions by local foundations indicates a vibrant local partnership ecosystem | Selection of major non-profit institutions in GE & VD and analysis of the share of funding coming from (local) foundations | Desk research; survey of major institutions | N/A | |

Each of the indicators listed above was evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively: the result then needed to be evaluated as positive or not in terms of promoting sector vitality. For example, is an observed level of diversity in boards, or a certain number of identified collaborative platforms, at the level that the sector should aspire to be? The project steering committee built consensus around three potential ratings: three stars for high, two stars for moderate and one star for low. These three potential ratings were applied to both the quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the qualitative perception survey, ratings were assigned as follows: high when more than 50% of respondents agreed or agreed strongly, low when fewer than 50% of respondents agreed or agreed strongly, and moderate for results in between. When the qualitative and quantitative results for the same indicator differed, the project team assigned an overall ranking for the indicator on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the reasoning and data behind each of the two ratings.

Independently of the proposed ratings, however, we encourage all sector stakeholders to make their own interpretation of the indicator result, and to take action where they see most development opportunities according to their own baseline of performance.

Public Opinion Survey Methodology

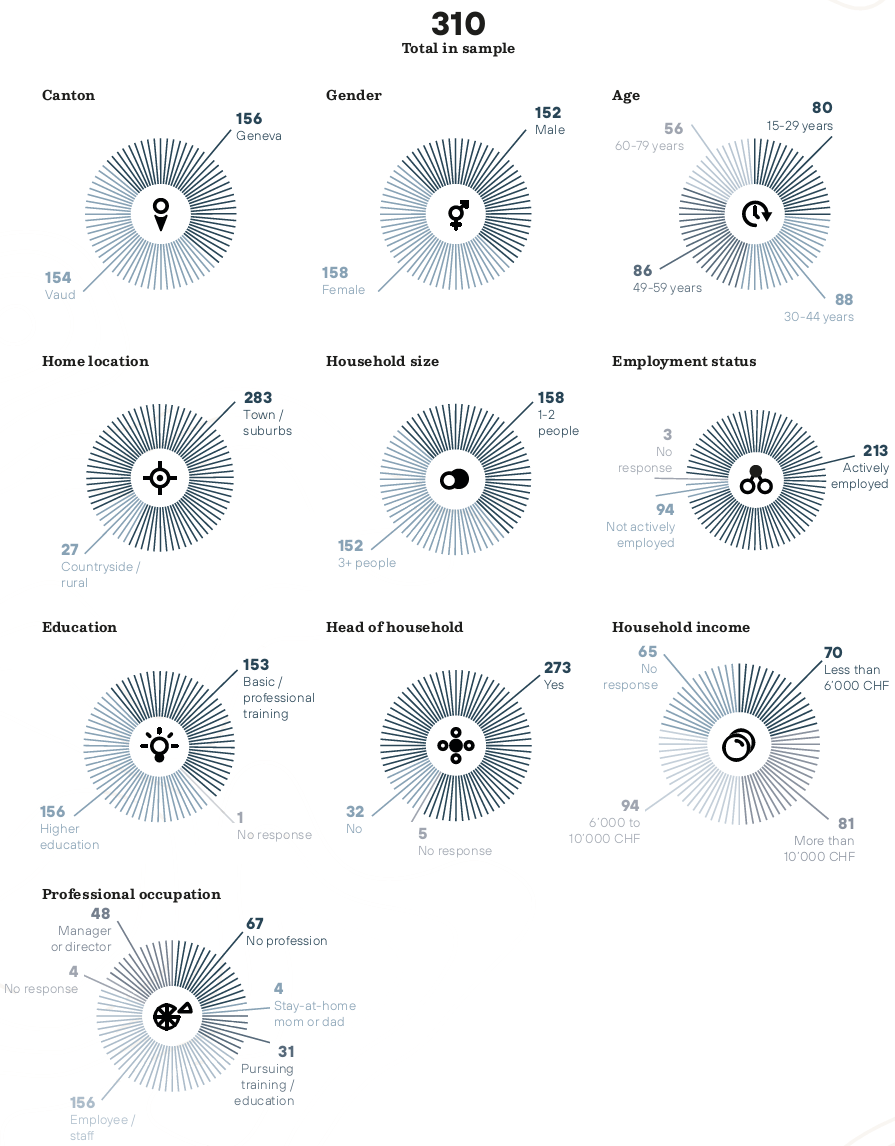

Due to the lack of data available on the public’s trust and general understanding of public utility foundations, the LINK Institut was requested to perform a public opinion survey of the general population in Geneva and Vaud, drawn from a pool of 27,000 potential respondents in Suisse Romande between the ages of 15-79. The final sample included 310 people, and, as noted in the text of the main report, the margin of error for the full survey results is +/- 5.7%.

The LINK results in this section represent a sample size of 310 residents in Geneva and Vaud. Descriptive statistics of the sample are in Figure 12. The questions that were asked to the interviewees are listed in Figure 11; please note that, as the Lemanic region is francophone, the questions were asked in French during the survey.

Figure 11: LINK Institut survey questions

In your opinion, what is a public utility foundation? Selon vous, qu’est-ce qu’une fondation d’utilité publique ?

To what extent do you agree with the following statement: Foundations work for the public interest in the Lemanic region. Dans quelle mesure êtes-vous d’accord avec l’affirmation suivante ? Les fondations oeuvrent pour l’intérêt public dans la région lémanique.

Can you think of a specific contribution a public utility foundation has made in the Lemanic region? Avez-vous connaissance d’une contribution spécifique faite par une fondation d’utilité publique dans la région lémanique ?

Below is a list of institutions. For each one, please indicate how much you trust that institution to do what is right using a nine-point scale where one means that you “do not trust them at all” and nine means that you “trust them a great deal.” 9-point scale (Institutions: NGOs, Business, Government, Media, Public utility foundations) Voici une liste d’institutions. Dans quelle mesure faites-vous confiance à chacune d’entre-elles pour agir de façon juste dans la région lémanique, sur une échelle de 1 à 9, où 1 signifie que vous ne lui faites « pas du tout confiance » et 9 signifie que vous lui faites « largement confiance » ? Institutions : ONGs, entreprises, gouvernement, médias, fondations d’utilité publique

Figure 12: Descriptive statistics of Geneva and Vaud public opinion survey sample.

Source: LINK Institut

Methodology Moving Forward: Potential Upgrading for Future Studies

Widening the Partner Group

Broadening the partner group in such studies in the future could strengthen vitality assessments even further. This exercise already benefited from extraordinary contributions. The Geneva DDE shared its foundation mapping effort, and this helped accelerate our analysis of online presence and accountability practices. The Geneva and Vaud foundation surveillance authorities shared new data on foundation assets and on the top risks emerging from their oversight activities. CEPS also opened its foundation database, sharing new information about board and staff numbers and diversity. Numerous intermediaries (see the full list under indicator 4.4 in Appendix 2) were also quite forthcoming in sharing information about the growth of their capacity in recent years, and several legal and fiscal experts weighed in on the regulatory context. SwissFoundations and proFonds, along with Fondation Lombard Odier, the GCP, FSG and the DDE, reached out to their respective contact lists for the perception survey, thereby giving over 500 representatives of foundations and other sector stakeholders the chance to evaluate the sector.

Such a partner group could become even more inclusive in the future. First and foremost, if the geographical range under study expands, the governmental representation would need to expand commensurately, including the additional cantons as well as, most likely, greater involvement of the Swiss federal government. We could also imagine a joint review of the legal and fiscal contexts between legal experts and the tax authorities. Increased inclusion of existing partners, such as the federal surveillance authorities in public reporting and risk analyses, as well as more intermediaries (such as AGFA), could also help strengthen the product of future iterations of the study. We would also welcome more funders to support and guide the work, as this pilot initiative required in-kind donations from all the members of the Steering Committee and project team.

Building out the Evidence Base

Connected to the composition and level of trust in the partner group is the opportunity to improve access to key data, as covered in our main recommendations. Foundation surveillance authorities, especially if coordinated between the cantonal and federal levels, could provide new levels of aggregate information, including on foundation spending. This would, of course, require appropriate resources, although resource needs could be diminished by leveraging partnerships with CEPS and/or the GCP. As mentioned above, our regulatory analyses could have been stronger if we had been able to consult with tax authorities at the cantonal and/or federal levels. Foundations themselves will likely become increasingly important sources of data: as more foundations join the global movement on philanthropic transparency, sector-wide analyses on many of our indicators will become more robust. Finally, we would expect to achieve higher stakeholder response rates to future versions of our perception survey, as awareness and trust grows about the relevance and usefulness of sector-wide assessments.

A few of the substantive areas of the report could also be augmented in the future should further data be made available:

- The analysis of board and staff composition and skill sets, which could help guide the educational priorities of academic centers and foundation associations by highlighting the existing capacities of the sector;

- Intermediaries’ staff capacities and the services they most commonly provide;

- Foundations’ key thematic focus areas and their differential allocations of resources across different themes; and

- Foundations’ key geographic areas, with the caveat that these can and do change frequently; this could help shed light on whether or not to philanthropy in the Lemanic region is more internationally oriented than in other parts of Switzerland, as many hypothesize.

Methodological Development Options

A core intent of the study was to create a methodology that could be replicated periodically to trigger new action to boost the sector’s vitality. Ideally, the same methodology would also be easily transferrable to other regions of Switzerland, and could even serve as an inspiration for other countries.

For future iterations of this assessment, it will be important to work with (many of) the same indicators, for comparison’s sake, while remaining open to additions to cover new areas of investigation. Two clear opportunities for methodological development have already surfaced, in addition to the points already noted above. First, while experts and/or publications did support the inclusion of all of the chosen indicators in the final report, the levels and depth of proof available varied from indicator to indicator. A subsequent iteration of the study could devote additional time to research in order to confirm or call into question some of the less-proven indicators. In addition, feedback on this first study and reactions from sector stakeholders will provide useful insights for future indicator selection.

Second, an entirely new category and set of indicators could be developed to focus on beneficiaries’ perspectives on the philanthropic sector. These indicators could, for example, examine the experiences that beneficiaries have when interacting with foundations, the degree to which foundations’ reporting requirements prove onerous for grant recipients, difficulties for beneficiaries in finding appropriate foundation partners, or several other pertinent issues. Despite the clear potential relevance, the perspectives of beneficiaries were not included in the present analysis due to time and resource constraints.

Planning for Efficient Geographical Expansion Incorporating Lessons Learned

Several factors will be key for any future expansions of the geographical scope of the study within Switzerland. To begin with, linguistic competency will naturally be paramount if the study is to expand significantly eastward. Another very important element of success will be prior consultation with all stakeholders, and in particular the types of organizations listed above as key sources of information. The goal of such a consultation would be to build consensus and excitement for the process and to establish the conditions for data sharing, as it becomes significantly harder to do so once the project is underway.

In summary, we believe that the present state of the methodology and study focus has significant power and was able to yield valuable insights to assess the state of philanthropic vitality in the two cantons under study. Nevertheless, it should be taken as a point of departure for how to rigorously and practically assess philanthropic vitality, rather than the endpoint in methodology development.